Generative Modeling with Energy-based Models Featured

Introduction

Generative modeling is the task of learning to generate new data samples that resemble a given dataset. This field has witnessed remarkable progress in recent years. Most existing generative modeling techniques can be broadly categorized by how they represent probability distributions:

-

Likelihood-based models directly learn the distribution’s probability density function via (approximate) maximum likelihood. Typical examples include autoregressive models, normalizing flow models, and variational auto-encoders (VAEs).

-

Implicit generative models represent the probability distribution implicitly through a model of its sampling process. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) are the most prominent example, where samples are synthesized by transforming random noise through a neural network.

Both approaches, however, have significant limitations. Likelihood-based models often require restrictive architectural constraints to ensure tractable normalization. Implicit models rely on adversarial training, which can be notoriously unstable and may lead to mode collapse.

In this post, I will introduce energy-based models (EBMs), a powerful paradigm for generative modeling that sidesteps many of these limitations. Energy-based models define probability distributions through an energy function. Their flexible formulation has made them foundational to many recent advances in machine learning, including connections to diffusion models and score-based generative modeling.

I will also introduce TorchEBM , a PyTorch library designed to make energy-based modeling accessible and efficient for both researchers and practitioners.

The Energy Function and Probability

The central idea behind energy-based models is elegantly simple. Instead of directly modeling a probability density function (which requires computing an often-intractable normalizing constant), we model an energy function $E_\theta(x) \in \mathbb{R}$ that assigns a scalar “energy” to each configuration $x$. The probability density is then defined as:

where $Z_\theta = \int e^{-E_\theta(x)} \, dx$ is the partition function (normalizing constant) that ensures the distribution integrates to one.

The key insight is that lower energy corresponds to higher probability. Points where the energy function takes small values are more likely under the model, while high-energy regions correspond to low probability.

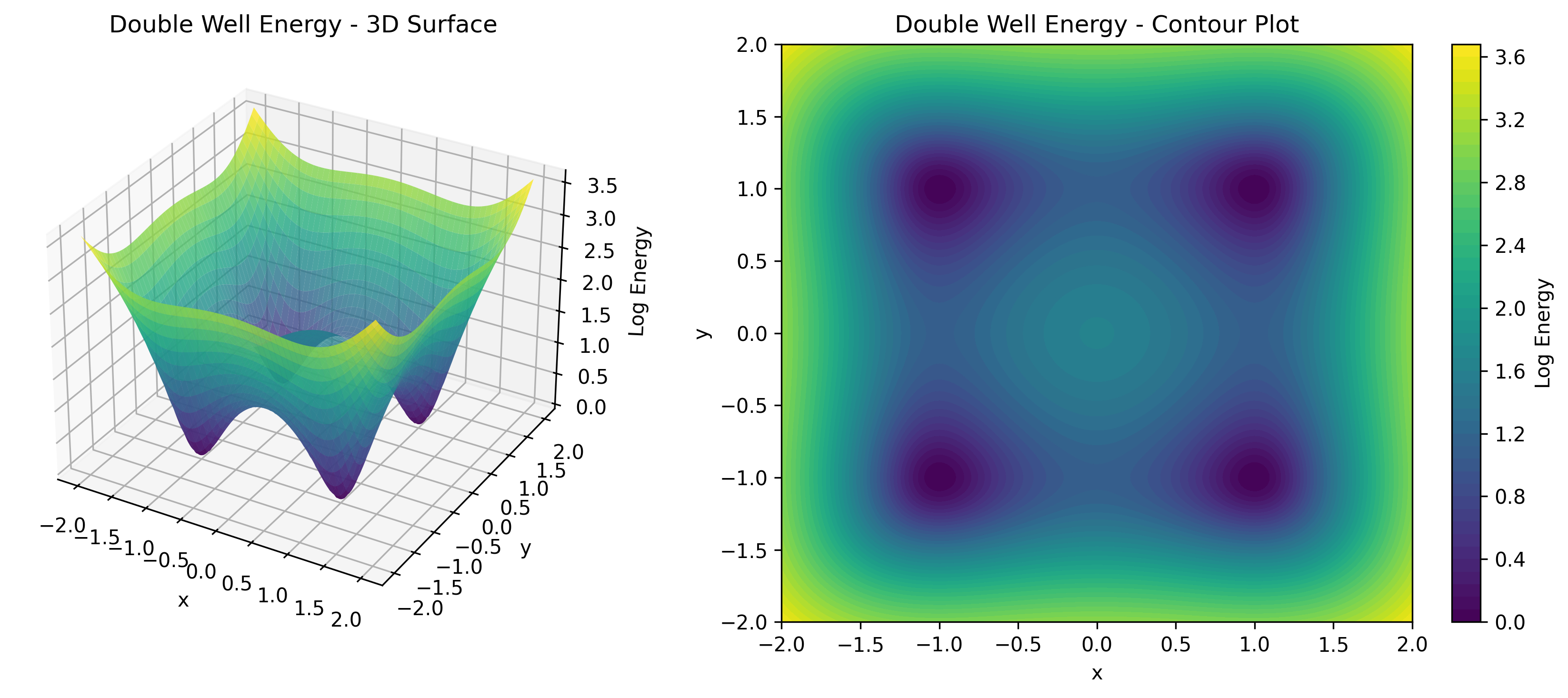

As shown in , this formulation offers remarkable flexibility. The energy function $E_\theta(x)$ can be parameterized by any neural network architecture without special constraints. We don’t need to worry about architectural restrictions that ensure tractable normalization. The price we pay is that the partition function $Z_\theta$ is typically intractable, which means we cannot directly compute likelihoods.

Here is the crucial observation: for sampling, we don’t need to know the partition function. Many powerful sampling algorithms, including Langevin dynamics and Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, only require access to the gradient of the energy function, $\nabla_x E_\theta(x)$, which is independent of $Z_\theta$ in .

The Score Function

Before diving into sampling, let us introduce an important quantity. The score function is defined as the gradient of the log probability density:

\[s_\theta(x) = \nabla_x \log p_\theta(x)\]For energy-based models, the score function has a particularly elegant form:

\[s_\theta(x) = \nabla_x \log p_\theta(x) = -\nabla_x E_\theta(x) - \underbrace{\nabla_x \log Z_\theta}_{=0} = -\nabla_x E_\theta(x)\]The score function is simply the negative gradient of the energy function. This independence from the partition function is what makes score-based methods so powerful. We can learn and use the score without ever computing the intractable normalizing constant.

The score function can be interpreted as a vector field pointing in the direction where the probability increases most rapidly. Following this vector field allows us to move from low-probability regions toward high-probability regions.

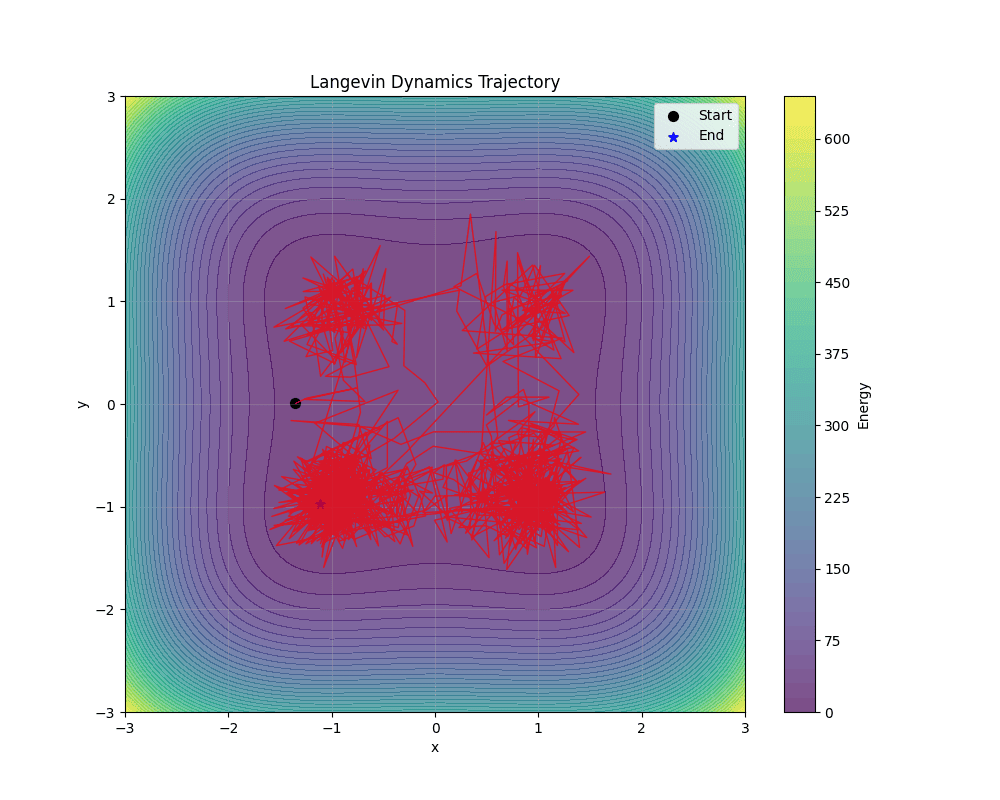

Sampling with Langevin Dynamics

Once we have an energy function (and thus access to its gradient), how do we generate samples from the distribution $p_\theta(x)$? The answer lies in Langevin dynamics, a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method that uses the score function to iteratively refine samples.

Langevin dynamics starts from an arbitrary initial point $x_0$ (often random noise) and iteratively updates according to the following rule:

where $\epsilon > 0$ is the step size and $z_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I)$ is standard Gaussian noise.

The update rule in has an intuitive interpretation. The gradient term $-\epsilon \nabla_x E_\theta(x_i)$ moves the sample toward lower energy (higher probability) regions. The noise term $\sqrt{2\epsilon} \, z_i$ injects stochasticity to enable exploration and ensure proper sampling.

Under certain regularity conditions, as $\epsilon \to 0$ and $K \to \infty$, the distribution of $x_K$ converges to the target distribution $p_\theta(x)$. In practice, we use finite step sizes and iteration counts, which introduces some approximation error that is negligible when $\epsilon$ is small enough and $K$ is large enough.

Training Energy-Based Models

Now comes the central challenge. How do we learn an energy function $E_\theta(x)$ from data? Given a dataset ${x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_N}$ drawn from an unknown data distribution $p_{\text{data}}(x)$, we want to adjust the parameters $\theta$ so that $p_\theta(x)$ approximates $p_{\text{data}}(x)$.

The maximum likelihood objective would have us minimize the following:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = -\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[E_\theta(x)] + \log Z_\theta\]Taking the gradient with respect to $\theta$:

\[\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_\theta}[\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]\]This gradient has an intuitive interpretation. The first term pushes down the energy of real data points, and the second term pushes up the energy of samples from the model.

The challenge is that the second expectation requires sampling from $p_\theta(x)$, which is itself the distribution we’re trying to learn.

Contrastive Divergence

Contrastive Divergence (CD) approximates this gradient by running a short MCMC chain (typically $k$ steps of Langevin dynamics) starting from real data points. Rather than running the chain to convergence, CD uses the samples after only a few steps. The procedure works as follows. First, we start with a real data point $x^{(0)} = x_{\text{data}}$. Then, we run $k$ steps of Langevin dynamics to obtain $x^{(k)}$. Finally, we approximate the gradient as:

\[\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta) \approx \nabla_\theta E_\theta(x_{\text{data}}) - \nabla_\theta E_\theta(x^{(k)})\]Persistent Contrastive Divergence (PCD) improves upon this by maintaining a persistent replay buffer of samples across training iterations. Instead of always initializing the MCMC chain from data, PCD continues the chains from where they left off in the previous iteration. This allows for better mixing and more accurate gradient estimates.

Parallel Tempering CD runs multiple MCMC chains at different “temperatures” (energy scales) and exchanges samples between them. Higher-temperature chains explore the space more freely, and lower-temperature chains provide accurate samples. This helps overcome the slow mixing that plagues standard CD when energy barriers separate modes.

Score Matching

An alternative to contrastive divergence is score matching, which learns the score function directly without requiring MCMC sampling. The key idea is to minimize the Fisher divergence between the data and model distributions:

\[\mathcal{J}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}(x)}\left[\left\| \nabla_x \log p_{\text{data}}(x) - s_\theta(x) \right\|^2\right]\]Remarkably, this objective can be rewritten in a form that doesn’t require knowledge of the data score $\nabla_x \log p_{\text{data}}(x)$:

\[\mathcal{J}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}(x)}\left[\text{tr}(\nabla_x s_\theta(x)) + \frac{1}{2}\|s_\theta(x)\|^2\right] + \text{const}\]where $\text{tr}(\nabla_x s_\theta(x))$ is the trace of the Jacobian (sum of second derivatives).

Several variants make score matching more practical. Denoising Score Matching adds noise to data and learns to denoise, avoiding explicit Jacobian computation. Sliced Score Matching approximates the trace using random projections, making it scalable to high dimensions.

Equilibrium Matching

A more recent approach called equilibrium matching provides yet another way to train EBMs. Rather than explicitly running MCMC during training, equilibrium matching learns by matching the model’s equilibrium distribution to the data distribution through a carefully designed loss that doesn’t require negative samples. This can significantly speed up training while maintaining sample quality.

Connection to Diffusion Models

Energy-based models have deep connections to the recently successful diffusion models and score-based generative models. In fact, both can be viewed as different perspectives on the same underlying framework.

Score-based generative models perturb data with multiple scales of noise and learn the score function at each noise level. By gradually decreasing the noise scale during sampling (a process called annealed Langevin dynamics), these models can generate high-quality samples comparable to or better than GANs.

When the number of noise scales approaches infinity, the perturbation process becomes a continuous-time stochastic differential equation (SDE). The remarkable insight is that any SDE has a corresponding reverse SDE that can generate samples by denoising, and this reverse SDE depends on the score function.

Stochastic Interpolants

A key concept bridging these ideas is that of stochastic interpolants, which are parameterized paths between a simple noise distribution and the data distribution. These interpolants define how to smoothly transform noise into data samples:

where $x_1$ is a data point, $\alpha(t)$ and $\sigma(t)$ are schedules controlling the interpolation, and $t \in [0, 1]$. At $t=0$, we have pure noise; at $t=1$, we recover the data.

Different schedule choices in lead to different generative processes. The linear interpolant uses $\alpha(t) = t$ and $\sigma(t) = 1 - t$. The variance-preserving (VP) schedule maintains unit variance throughout the path. The cosine schedule provides smoother transitions that often improve sample quality.

TorchEBM provides implementations of these interpolants and the numerical integrators needed to solve the corresponding SDEs.

TorchEBM provides the building blocks for both energy-based and score-based approaches. The library includes loss functions such as contrastive divergence, score matching, and equilibrium matching. It also provides MCMC samplers including Langevin dynamics, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, and gradient descent variants. For continuous-time models, TorchEBM offers SDE integrators like Euler-Maruyama, Heun (second-order), and Leapfrog. Additionally, the library includes interpolants for linear, cosine, and variance-preserving schedules, as well as flow samplers for trained diffusion and flow-matching models.

TorchEBM: A Practical Toolkit

To make these ideas accessible and practical, we developed TorchEBM, a high-performance PyTorch library for energy-based modeling. The library provides a modular, flexible framework for defining energy functions, sampling, and training.

Core Components

TorchEBM is organized around several key components:

Energy Functions: Define custom energy functions by subclassing BaseModel, or use built-in analytical functions for testing:

import torch

from torchebm.core import GaussianModel

from torchebm.samplers import LangevinDynamics

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Define a Gaussian energy function

model = GaussianModel(mean=torch.zeros(2), cov=torch.eye(2), device=device)

# Create a Langevin dynamics sampler

sampler = LangevinDynamics(model=model, step_size=0.01, device=device)

# Generate samples

initial_points = torch.randn(500, 2, device=device)

samples = sampler.sample(x=initial_points, n_steps=100)

Samplers: The library provides MCMC algorithms for drawing samples from energy distributions. LangevinDynamics offers gradient-based sampling with noise injection, and HamiltonianMonteCarlo uses Hamiltonian dynamics for more efficient exploration.

Loss Functions: TorchEBM provides a comprehensive suite of training objectives.

For the Contrastive Divergence Family, the library includes ContrastiveDivergence (standard CD-k with configurable MCMC steps), PersistentContrastiveDivergence (maintains persistent sample chains across iterations), and ParallelTemperingCD (multi-temperature MCMC for better mode exploration).

For the Score Matching Family, the library provides ScoreMatching (explicit score matching with Jacobian computation), SlicedScoreMatching (scalable approximation using random projections), and DenoisingScoreMatching (learns to denoise, avoiding explicit Jacobians).

Other methods include EquilibriumMatchingLoss, a modern approach without negative sampling.

Synthetic Datasets: For testing and visualization, TorchEBM includes TwoMoonsDataset, GaussianMixtureDataset, SwissRollDataset, EightGaussiansDataset, CheckerboardDataset, PinwheelDataset, CircleDataset, GridDataset, and more.

Training Example

Here’s a complete example of training an EBM on a 2D dataset:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.optim as optim

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader

from torchebm.core import BaseModel

from torchebm.samplers import LangevinDynamics

from torchebm.losses import ContrastiveDivergence

from torchebm.datasets import TwoMoonsDataset

# Define a neural energy function

class MLPEnergy(BaseModel):

def __init__(self, input_dim: int, hidden_dim: int = 64):

super().__init__()

self.net = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(input_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.SiLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.SiLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 1),

)

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

return self.net(x).squeeze(-1)

# Setup

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

model = MLPEnergy(input_dim=2).to(device)

sampler = LangevinDynamics(model=model, step_size=0.1, device=device)

loss_fn = ContrastiveDivergence(

model=model, sampler=sampler, k_steps=10, persistent=True

)

optimizer = optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=1e-3)

dataset = TwoMoonsDataset(n_samples=3000, noise=0.05)

dataloader = DataLoader(dataset, batch_size=128, shuffle=True)

# Training loop

for epoch in range(100):

for batch_data in dataloader:

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss, negative_samples = loss_fn(batch_data.to(device))

loss.backward()

torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(model.parameters(), max_norm=1.0)

optimizer.step()

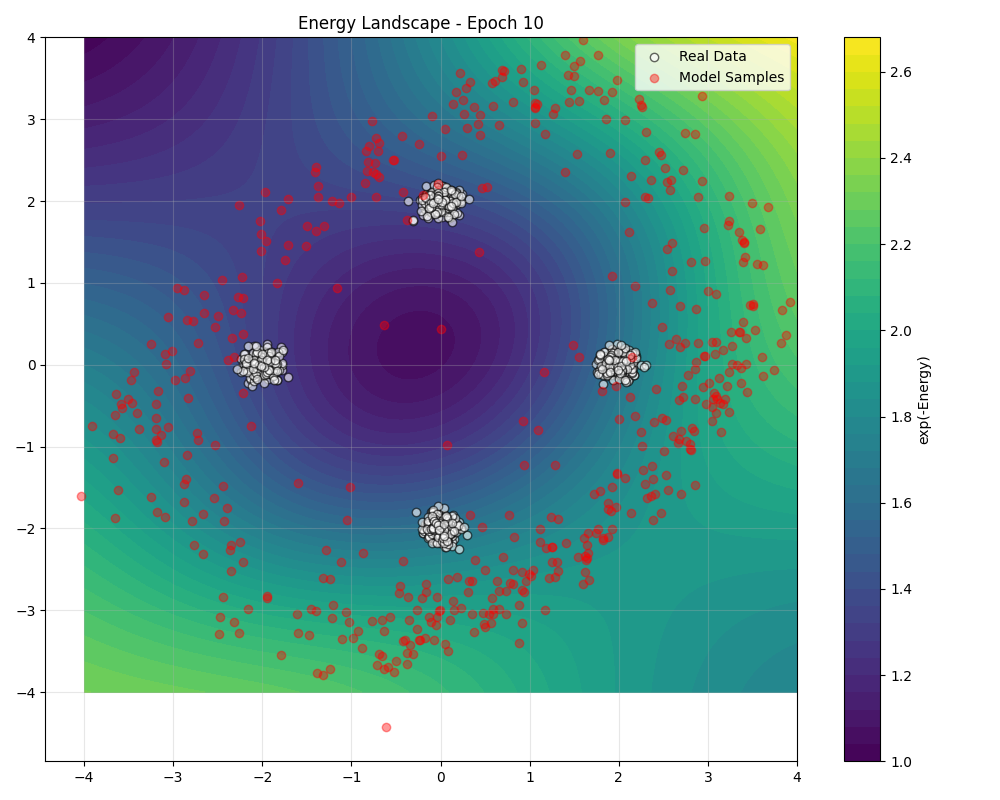

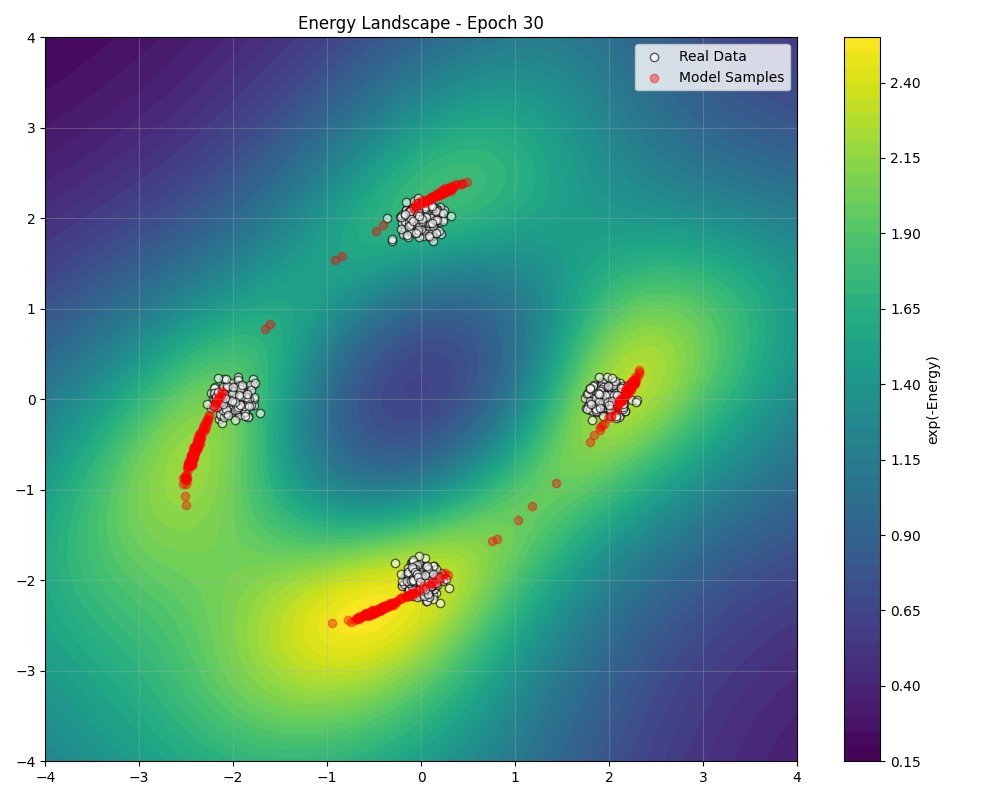

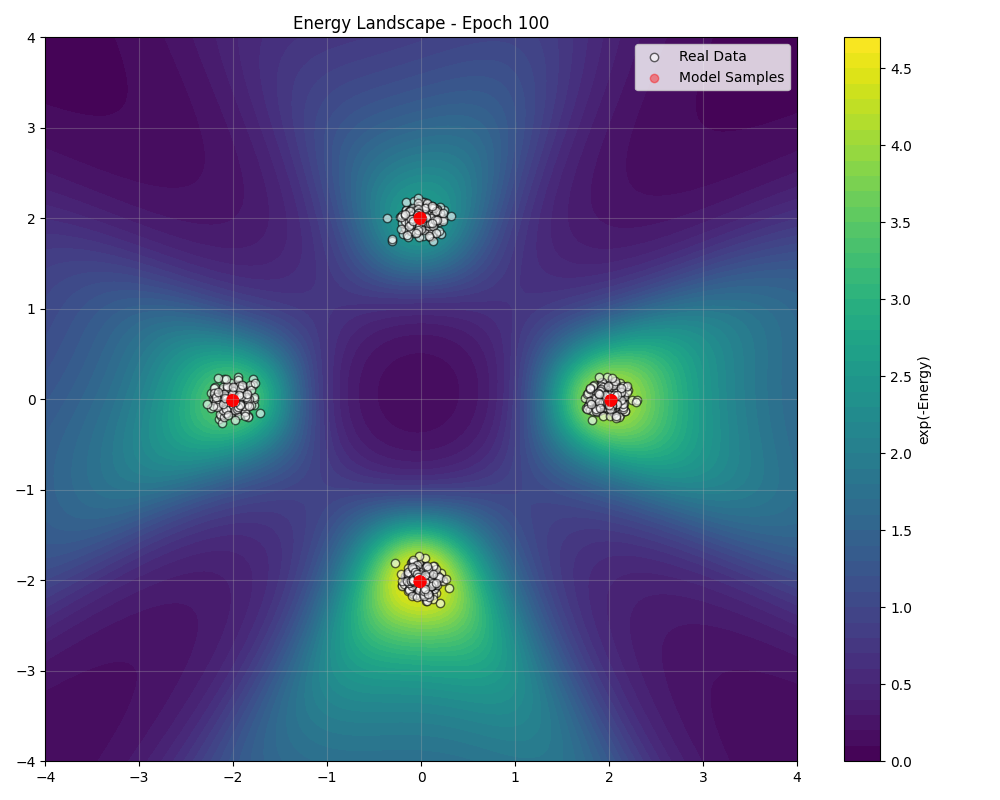

During training, we can visualize how the energy landscape evolves to match the data distribution ():

Sampling Algorithms

TorchEBM provides a rich collection of sampling algorithms, each suited to different scenarios.

MCMC Samplers

Langevin Dynamics is the workhorse of EBM sampling, using gradient information with injected noise to explore the energy landscape (see ). As discussed earlier, it provides asymptotically exact samples under mild conditions.

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) introduces auxiliary momentum variables and uses Hamiltonian dynamics to make proposals that can traverse large distances in the state space while maintaining high acceptance rates.

The idea is to define a joint distribution over positions $x$ and momenta $p$:

where $M$ is a mass matrix (often the identity). The Hamiltonian dynamics preserve the joint distribution defined by , allowing us to make distant proposals that are still likely to be accepted.

from torchebm.samplers import HamiltonianMonteCarlo

hmc_sampler = HamiltonianMonteCarlo(

model=model,

step_size=0.1,

n_leapfrog_steps=10,

device=device

)

samples = hmc_sampler.sample(x=torch.randn(500, 2, device=device), n_steps=100)

HMC is particularly useful in several scenarios. It works well for distributions with strong correlations between dimensions. It also performs efficiently in high-dimensional problems where random-walk behavior is inefficient. Additionally, it handles cases where the energy landscape has complex geometry.

Gradient Descent Samplers

For deterministic optimization or mode-finding, TorchEBM provides gradient descent samplers. GradientDescentSampler implements pure gradient descent toward energy minima. NesterovSampler uses Nesterov accelerated gradient descent for faster convergence.

These are useful when you want to find the most probable configurations (modes) rather than sample from the full distribution:

from torchebm.samplers import GradientDescentSampler, NesterovSampler

# Find energy minima

gd_sampler = GradientDescentSampler(model=model, step_size=0.01, device=device)

modes = gd_sampler.sample(x=torch.randn(100, 2, device=device), n_steps=500)

# Accelerated version

nesterov_sampler = NesterovSampler(model=model, step_size=0.01, momentum=0.9, device=device)

modes = nesterov_sampler.sample(x=torch.randn(100, 2, device=device), n_steps=200)

Flow Samplers

For trained generative models such as diffusion and flow matching models, the FlowSampler generates samples by solving an ODE or SDE from noise to data:

from torchebm.samplers import FlowSampler

from torchebm.interpolants import LinearInterpolant

from torchebm.integrators import HeunIntegrator

interpolant = LinearInterpolant()

integrator = HeunIntegrator()

flow_sampler = FlowSampler(

model=trained_velocity_model,

interpolant=interpolant,

integrator=integrator,

device=device

)

samples = flow_sampler.sample(batch_size=256, n_steps=50)

SDE Integrators

When working with continuous-time generative models, we need numerical integrators to solve stochastic differential equations. TorchEBM provides several options, as shown in .

| Integrator | Order | Description |

|---|---|---|

EulerMaruyamaIntegrator |

1st | Simple, fast, but less accurate |

HeunIntegrator |

2nd | Predictor-corrector, better accuracy |

LeapfrogIntegrator |

2nd | Symplectic, used in HMC |

The Euler-Maruyama method is the stochastic analog of Euler’s method for ODEs:

The Heun integrator (also known as improved Euler or RK2) provides second-order accuracy by using a predictor-corrector approach, often yielding better sample quality with fewer steps.

from torchebm.integrators import EulerMaruyamaIntegrator, HeunIntegrator

# First-order (faster)

euler_integrator = EulerMaruyamaIntegrator()

# Second-order (more accurate)

heun_integrator = HeunIntegrator()

Interpolants for Flow Matching

Interpolants define the path between noise and data in flow-based models. TorchEBM supports several schedules ():

| Interpolant | Schedule | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

LinearInterpolant |

$\alpha(t) = t$ | Simple, widely used |

CosineInterpolant |

Cosine schedule | Smoother transitions |

VariancePreservingInterpolant |

VP-SDE | Diffusion models |

from torchebm.interpolants import LinearInterpolant, CosineInterpolant, VariancePreservingInterpolant

# Choose based on your model architecture

linear = LinearInterpolant()

cosine = CosineInterpolant()

vp = VariancePreservingInterpolant()

# Interpolate between noise (x0) and data (x1) at time t

x_t = linear.interpolate(x0=noise, x1=data, t=0.5)

Practical Considerations

Training energy-based models can be challenging. Here are some practical recommendations based on the literature and our experience developing TorchEBM.

Gradient Clipping

EBM gradients can be unstable, especially early in training. Always use gradient clipping:

torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(model.parameters(), max_norm=1.0)

Parameter Scheduling

Dynamic adjustment of sampling parameters can improve training stability. TorchEBM provides schedulers for step size and noise scale:

from torchebm.core import CosineScheduler

step_scheduler = CosineScheduler(start_value=0.1, end_value=0.01, n_steps=100)

sampler = LangevinDynamics(model=model, step_size=step_scheduler, device=device)

Persistent Chains

Using persistent contrastive divergence with a replay buffer significantly improves training quality by allowing MCMC chains to mix properly across iterations.

Regularization

Energy functions can collapse (producing very negative energies everywhere). Consider applying weight decay on network parameters, spectral normalization on layers, or energy regularization penalties.

Built-in Energy Functions

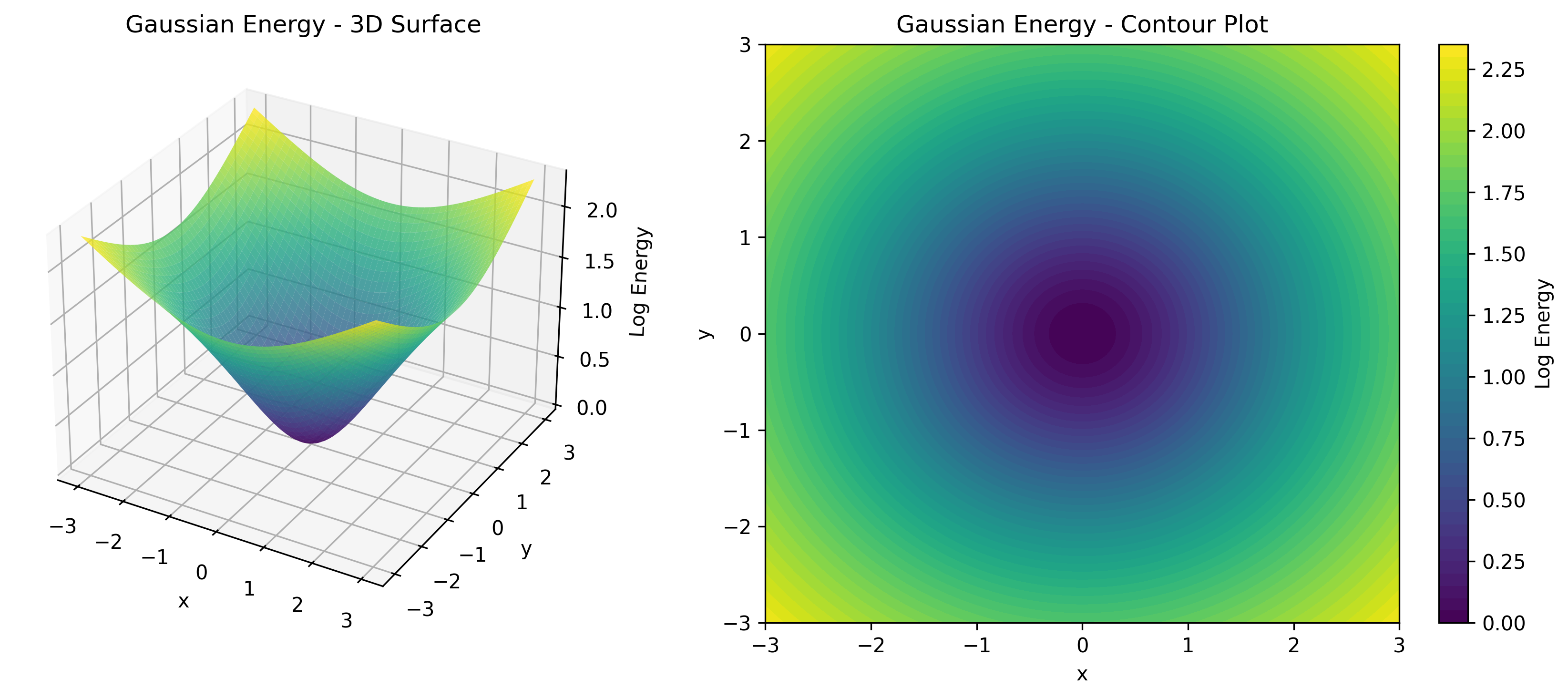

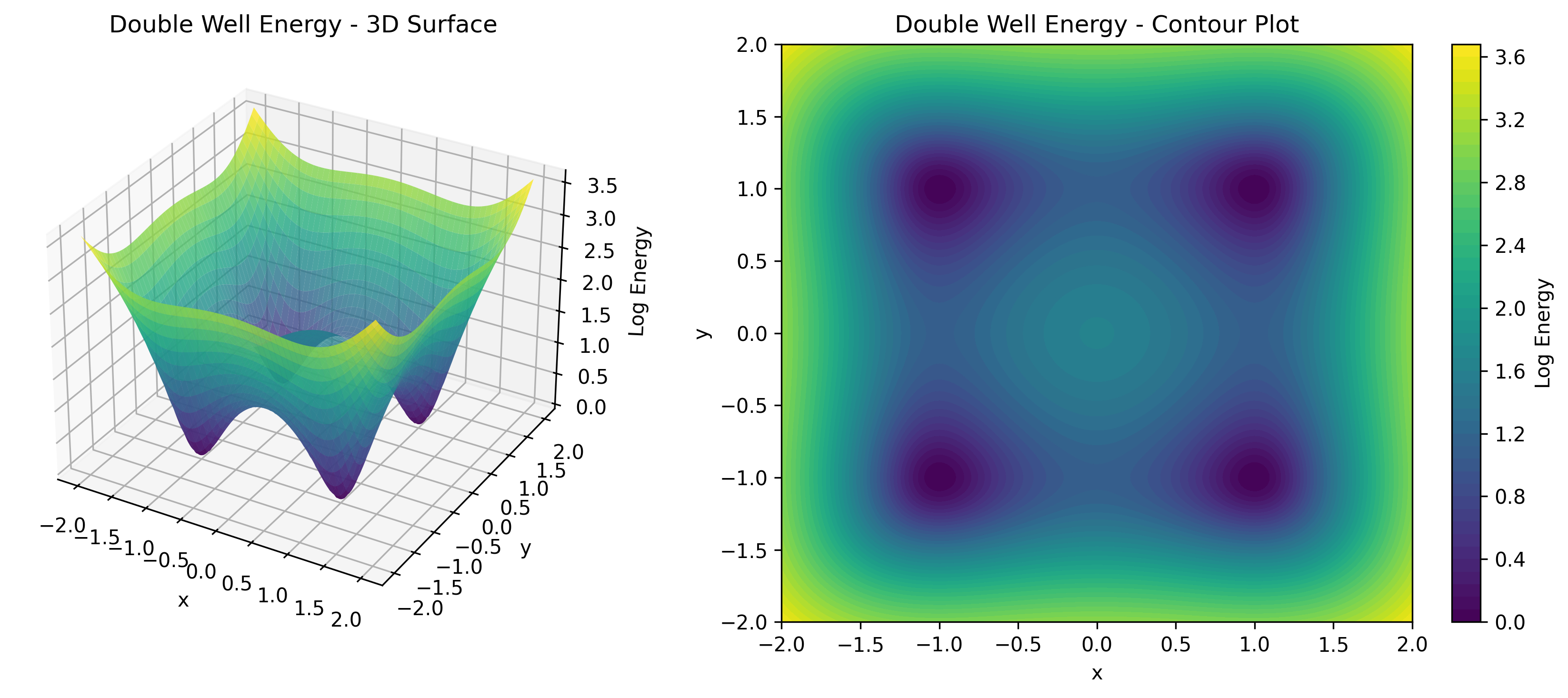

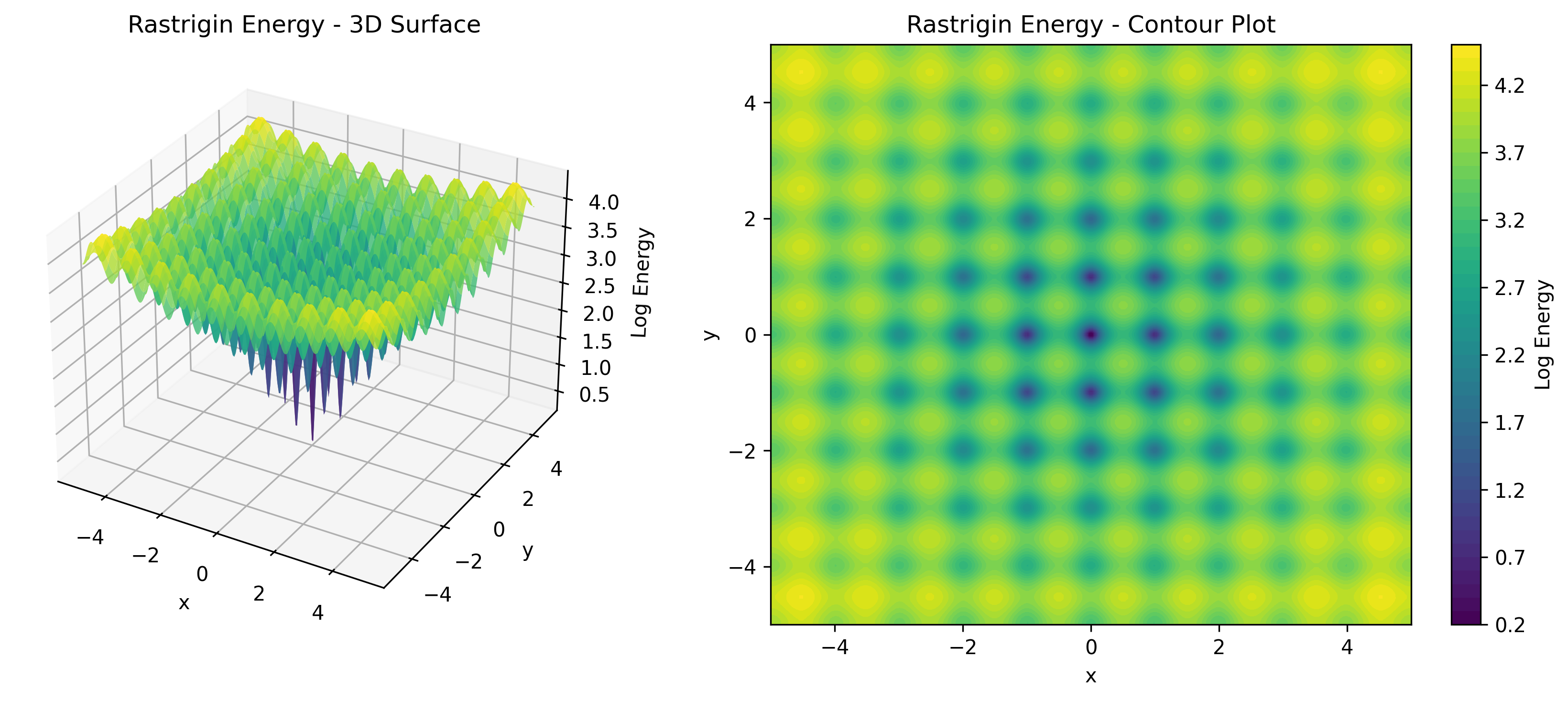

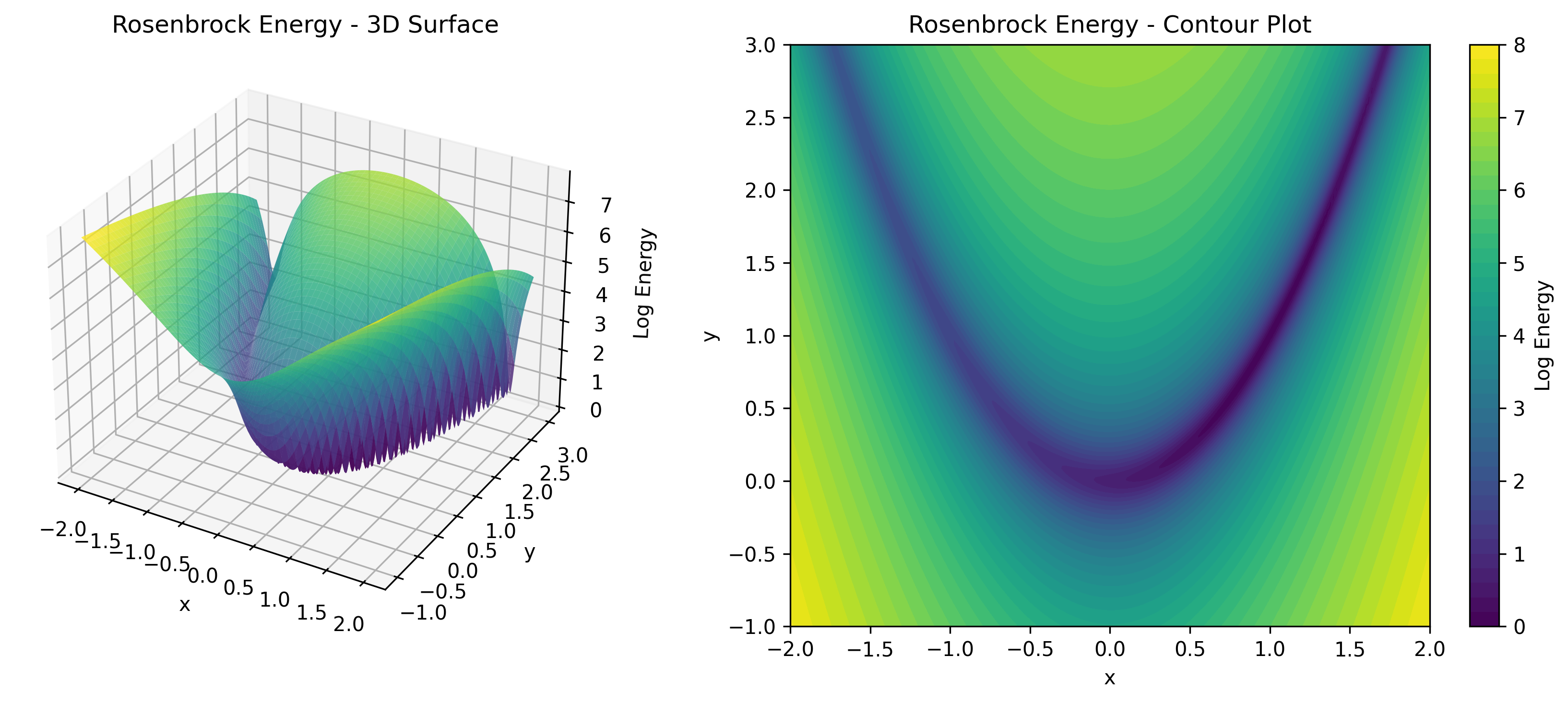

TorchEBM includes analytical energy functions useful for testing and benchmarking, as illustrated in .

| Energy Function | Description | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

GaussianModel |

Multivariate Gaussian | Baseline testing |

DoubleWellModel |

Bimodal with energy barrier | Multimodal sampling |

RastriginModel |

Many local minima | Optimization benchmarks |

RosenbrockModel |

Curved valley (banana) | Testing gradient following |

AckleyModel |

Multimodal with global minimum | Global optimization |

HarmonicModel |

Harmonic oscillator | Physics simulations |

Complete API Summary

TorchEBM provides a comprehensive toolkit organized into modular components ():

| Category | Components | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Losses (CD) | ContrastiveDivergence, PersistentContrastiveDivergence, ParallelTemperingCD |

MCMC-based training |

| Losses (Score) | ScoreMatching, SlicedScoreMatching, DenoisingScoreMatching |

Score-based training |

| Losses (Other) | EquilibriumMatchingLoss |

Equilibrium-based training |

| Samplers (MCMC) | LangevinDynamics, HamiltonianMonteCarlo |

MCMC samplers |

| Samplers (Optim) | GradientDescentSampler, NesterovSampler |

Optimization-based |

| Samplers (Flow) | FlowSampler |

Diffusion/flow models |

| Integrators | EulerMaruyamaIntegrator, HeunIntegrator, LeapfrogIntegrator |

SDE numerical solvers |

| Interpolants | LinearInterpolant, CosineInterpolant, VariancePreservingInterpolant |

Noise schedules |

| Models | ConditionalTransformer2D, AdaLNZeroBlock, LabelClassifierFreeGuidance |

Neural architectures |

| Datasets | TwoMoonsDataset, EightGaussiansDataset, SwissRollDataset, ... |

Synthetic data |

| Schedulers | CosineScheduler, LinearScheduler, ExponentialDecayScheduler, ... |

Parameter scheduling |

Concluding Remarks

Energy-based models offer a principled and flexible approach to generative modeling. By learning an energy function rather than directly parameterizing a normalized density, we gain several benefits.

Flexibility means any neural network architecture can serve as an energy function. Interpretability comes from the fact that energy values have a clear probabilistic interpretation. Connections refer to the deep links to statistical physics, score-based models, and diffusion models.

The main challenges of intractable normalization and the need for MCMC sampling have been addressed through techniques like contrastive divergence and score matching, making EBMs increasingly practical for real-world applications.

TorchEBM provides the tools needed to experiment with these ideas. Whether you’re exploring energy-based models for research or building practical applications, the library offers modular components for energy functions, samplers, and loss functions. It also provides GPU acceleration for efficient sampling and training, along with comprehensive documentation, examples, active development, and community support.

Getting Started

Install TorchEBM with pip:

pip install torchebm

Explore the documentation and tutorials at the following links.

Citation

If TorchEBM contributes to your research, please consider citing .

TorchEBM is open source under the MIT License. Contributions are welcome!

GitHub · Documentation · PyPI